I only have ice for you...

‘Ice navigation’

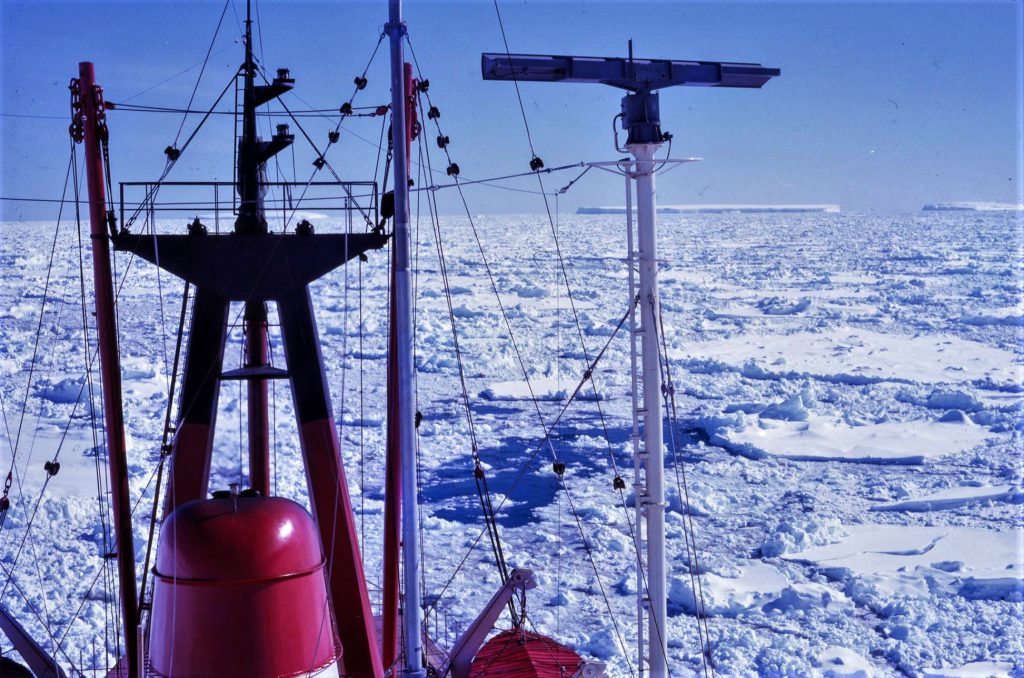

Ice navigation is risky business. Some of the worst disasters at sea have been caused by ice, and in the general perception, the name of the Titanic will forever epitomize the story of treacherous icebergs and death by cold.

It takes highly specialized knowledge and experience to navigate in icy waters, both outside and within the boundaries of the ice. Many have attempted to describe the challenges of ice navigation. One of the more experienced navigators summed up the key points in these three golden rules:

- Rule no. 1: avoid the ice

- Rule no. 2: avoid the ice

- Rule no. 3: avoid the ice

If it is not possible to comply with these rules, proceed with extreme vigilance and caution. To put the guidelines in the simplest possible terms. A common misunderstanding concerning ice, which, unfortunately, is common in many contexts, even today, is that ‘ice is ice’.

The hazards of ice navigation never let go, even for a second. So obviously, ice floes, large chunks and entire icebergs have always been important dangers to look out for.

Photo by Rasmus Nygaard

Joanne Verikios's archive

Photo by Rasmus Nygaard

‘Her Majesty in the ice’

The Nella Dan could not, and was not supposed to, avoid the ice. Her task was making it through the ice, but she was no icebreaker – and at 2200 horsepower, she hardly had the raw power to push through ice measuring more than 1.5 metres in thickness. Today, increasingly, polar ships are constructed as icebreakers and equipped with a very different level of engine power and technology than was available in 1960.

As a ship of her time, Nella Dan was built to twist and yield in her agile dance with the solidified sea. This was a ship that needed to be handled by experienced seamen and navigators with the right skills to make the most of what she had to offer. The construction of the hull, with the icebreaker stern and class-A reinforcements, made her strong enough to withstand the pressure – even, if necessary, popping out of the ice when she was frozen in.

In other words, Nella was built to last – and she took many a beating during her years of service, struggling through the ice. Naturally, the ice took its toll on the ship, and over the years, the hull had many metres of steel replaced after rough seasons in the Arctic and Antarctic.

Crew after crew developed a sense for ‘Miss Nella’s feeling for ice’, whether old pack ice, glacier ice, new sea ice or blue ice. The make-up and nature of ice varies considerably, and navigation always required the utmost vigilance. Good communication between the crow’s nest, the bridge, the engine and ice reconnaissance from planes, satellites or helicopters could make the difference between success and failure on a voyage.

During the early Antarctic season (October/November), ships might encounter the sea ice as far north as 6-8 latitudes or almost 1,000 km before the Antarctic landmass. That made for a long trip to the coast if the ship wound up in ice that was moving counter to the intended course.

Spending days and weeks navigating ice-filled water is an unforgettable experience. Sometimes crisp and crunchy like high-quality chocolate, sometimes as a gooey jelly of wet pancake ice. Sometimes the ship crashes into floes and chunks scraping and grating along the hull; sometimes the ship shrieks under the pressure and makes scant progress.

Sometimes, days and nights go by where all the look-out has to report is, ‘I only have ice for you.’

Postcard from the ice

Season after season, crews and guests on board have been spellbound by the ice, the sea and the photogenic little ship. Red, white and blue. Simple, bright and brilliant.

‘Am I really a part of this?’ varying photographers asked themselves. These images are postcards plucked from the moment, with no need for subsequent photoshopping or multiple attempts. A roll of film had 36 shots, and the nearest camera shop was a long way away.

These are photos captured by eyes that see and by senses that are wide open to the immediate beauty of the surroundings in form, colour, contrast and endless spaces.

Contemporary ice navigation

By Henrik Hartlev Jeppesen

Shipmaster, teaches ice navigation at SIMAC, Svendborg International Maritime Academy. A trainee mate during Nella Dan’s last season in 1987.

Dansk polarfart 1915-2015 (Danish polar sailing 1915–2015)

By Bjarne Rasmussen, former mate in Arctic and Antarctic waters.

The book deals with Danish ships running to Greenland, St. Lawrence and arctic Canada and navigating the North-East and North-West Passages. The main focus of the book is on the role of Danish government institutions, such as Royal Greenland Trade Department (Kongelige Grønlandske Handel, KGH) and private shipping companies, in the development of Greenland’s maritime infrastructure after 1945.